Toledo Police Museum

Open every Saturday from 10:00 am until 4:00 pm. Free Admission.

In 1867, Ohio legislature passed the Metropolitan Police Law which required a full time paid police force for the City of Toledo. At 8 AM on April 27, 1867, the "MP's" as they were respectfully called by the public, took charge of policing the City of Toledo.

PAST SPOTLIGHTS

The Toledo Police Museum collects, preserves, and makes accessible records and items of enduring value concerning the Toledo Police Department. Though many items have great value, the limitation of physical space for display makes it impossible for all items to be exhibited.

SPOTLIGHT is the Toledo Police Museum's digital endeavor to tell the story of these archived items. We "spotlight" these items in an enthusiastic attempt to share the broader picture with you. We hope you enjoy.

SPOTLIGHT ON THE 1979 CITY WIDE STRIKE

July 1, 1979

As negotiations broke down around 8 p.m. on June 30, 1979, the city prepared to go to court on Monday to get an injunction against walkouts in the police, fire, water and sewage departments. In an unprecedented show of union strength and solidarity, a very tough call was made by city workers, including the police department. City workers walked off the job early on the rainy Sunday morning of July 1, 1979. On this 45 year anniversary, we look back at this tumultuous time; what happened and what were the consequences. Click here for a newspaper history of the strike.

Because police, fire and other municipal strikes have the capability of igniting anarchy, in 1983 the Ohio Public Employees’ Collective Bargaining Act was created to promote order and stability in public sector labor relations.

SPOTLIGHT ON THE 1918 SPANISH FLU PANDEMIC

On September 19, 1918, Toledoans were “cautioned to take the strictest precaution to prevent Spanish influenza getting even a toe-hold in Toledo”. (Toledo News Bee Sept 19, 1918)

Even though the article stated there had been no fatalities in Toledo to that point, a search of the newspaper in months prior finds numerous deaths of local citizens from pneumonia and other respiratory infections that, in retrospect, may have been the first signs that the flu had already arrived.

The similarities to COVID 19 in 2020 are stunning. Click on the photo of Officer Barbara Hunter, wearing a mandatory mask during the COVID outbreak, to discover how the City of Toledo, the Toledo Police Department, and the world responded to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

SPOTLIGHT ON CALL BOXES

Do you own a TPD call box? Find the number, click the photo to the left and discover where your box was posted in the city.

SPOTLIGHT ON DETECTIVE BACH'S BADGE

Click the above photo of Detective George Bach to read the report from Drs. Burt G. Chollett and Albert L. Bershon as to the condition of Det. Bach in 1937, 15 years after he was shot in the leg.

Click the photo of Detective Lieutenant William Martin to read more about him.

Retired Hanover Park, IL Police Officer Tony Konecki contacted the Toledo Police Museum after he came into possession of Detective George W. Bach's badge. His mother, Lee Konecki, was given the badge by George's niece, Audrey Bach.

George W. Bach was born on March 10, 1883. He was appointed to the Toledo Police Department on October 1, 1907 but that career was cut rather short after he was found intoxicated on duty and dismissed in July of 1909. In 1918 however, he was rehired and quickly assigned as a detective, an assignment that would change his life forever.

On September 10, 1922, in a story worthy of the big screen, Detective Lieutenant William “Dick” Martin and Detective George Bach went to a garage at Fulton and Prescott Streets in response to a report that three suspects had left a suspicious looking touring car there.

The detectives concealed themselves in the rear of the building, and shortly after 9 a.m. the suspects returned. When Martin and Bach confronted them, one of the suspects pulled a gun from his waistband and opened fire. Martin was shot below the heart. Bach was shot in the right thigh, and though wounded, returned fire, striking one of the suspects before they were able to flee.

For the next few days, newspaper headlines told of the thrilling capture of the “bandits” by armed citizens in Wauseon, Ohio, who used their wits and guns to hold the suspects hostage until law enforcement could take them into custody. The suspects were members of the notorious Barrows gang of bank robbers working out of Kansas City.

Bach wore the badge shown here on that fateful day. Five days later, Bach was promoted to Detective Sergeant and this badge would have been tucked away, replaced by a new one bearing his elevated rank.

Click here to read newspaper articles and history of this event.

Police and dry agents in both Detroit and Toledo struggled to keep up with the daily crime. Officers were often left out of touch for 30 minutes or more as they worked their beats between scheduled check-ins. It was not uncommon for an officer patrolling a beat to visit a home and use a private telephone to call in to the central police station.

Police department call boxes were helping fight the war on crime, but not all neighborhoods in a growing suburb had a box. Finding and using the nearest phone wasn’t enough. If a crime occurred, it was often faster for a citizen to yell “HELP! POLICE! POLICE!” and search on foot for the nearest patrolling officer.

The rise of organized crime during Prohibition created the urgency and necessity for law enforcement to incorporate emerging technology into daily operations – and it all converged in Detroit and Toledo.

The Development of Amateur Radio and Radio Broadcasting

On December 12th, 1901, the first radio transatlantic communication by Guglielmo Marconi took place, proving radio was more than just a scientific novelty for amateurs, and that it could accelerate communications between people and locations around the world.

SPOTLIGHT ON THE EARLY HISTORY OF RADIO DISPATCHED POLICING IN TOLEDO

By Steve Pietras, Joseph Boyle, Beth Thieman, Michelle Hall Wheaton

In the summer of 1921, Prohibition was in full effect and America had gone “dry” — a prime opportunity for bootleggers smuggling alcohol.

Back in that era, 911 systems didn’t exist, nor did instant film cameras. There were no cell phones or television, thus no such thing as a video surveillance system either. Radio broadcasting was in its infancy, two-way radios hadn’t been invented yet and only a few homes had telephones.

Catching Nearly Invincible Criminals

Underworld mobsters looking to take advantage of the Volstead Act, worked to fill America’s lust for alcohol. As speakeasies grew to fill that thirst, so did the hidden supply chain network that had the booze.

One such group was the “Purple Gang”, an extension of Al Capone’s Chicago mob stranglehold over the Midwest. The Purples ran rampant in the cities and suburbs of Detroit and Toledo. Though Gang Leader Thomas “Yonnie” Licavoli had once ordered Capone out of Detroit, they eventually worked out a partnership and made loads of money supplying Capone with a river of Canadian whiskey routed from Detroit through Toledo and west to Chicago.

As radio technology evolved from spark gap generators – emitting dots and dashes to vacuum tube voice communications – so did the application of radio.

Soon the idea of mass media was born. It was a medium that could provide the same communications as a newspaper without wires and without the need for a reprint should the news of the day suddenly change.

In November 1920, KDKA in Pittsburgh made its -debut by broadcasting presidential election results across the Midwest. For years it was believed and accepted that KDKA was the first station in the U.S., but documented history later

revealed WWJ in Detroit (then Amateur station 8MK) went on the air in August 1920. The debate raged until 1936 when the father of the vacuum tube Lee De Forest himself proclaimed 8MK was indeed first.

Detroit amateur operator Michael Lyons, who was paid to supervise the construction of WWJ, put 8MK on the air. Lyons was well known in the Detroit amateur radio community and was good friends with Edward H. Clark, another fellow radio amateur in Detroit.

Toledo Police and Radio Meet

In August 1920, WWJ radio began its first broadcasts in Detroit. Fledgling radio reports of the era included stories about the organized crime antics of “The Purple Gang”. Many of those same crimes were also occurring in Toledo, about 60 miles southwest of Detroit.

Toledo Police Chief Henry Herbert had invested city funds into anything that could prove to be an advantage in the hidden war on the streets. The fastest Marmon cars of the era, motorcycle cops, a state-of-the-art gun range, women detectives and even “sky patrol” airplanes were all employed to target the problem.

May 23, 1921, Amateur Radio station W8BNE in Detroit was attempting to transmit radio signals to Police vehicles without success. Lyons and Clark believed they had a better method to establish communications to a Police vehicle and needed a testing location. In August 1921, when Chief Herbert was contacted by the radio men Lyons and Clark from Michigan with a new crime fighting idea, they had his full attention.

Lyons and Clark wanted to test how radio communications could potentially be used to fight crime if they could prove and establish reliable vehicle communications. Interested, Chief Herbert agreed to meet the pair and green-lighted an experiment.

On August 24, 1921, Lyons and Clark installed a radio transmitter built by Clark at the Toledo Police Central station and configured a Toledo Police Marmon speed car with radio receiving gear mounted in the back seat.

Toledo Police Patrolman Albert Krueger was first assigned the specially equipped vehicle for field testing. Chief Herbert radioed the car to leave Monroe Street near Swayne Field. He told Kruger “Proceed to Detroit Ave and Dorr Street then phone in a report to headquarters”. That transmission marked the first use of a radio dispatched command to a patrol officer vehicle in the field.

Testing of the radio apparatus continued that day. Toledo Patrolman Strable who next drove the specially equipped police speed car on the city’s east side. He was on patrol near Woodville Street and received a radio call from the central station two miles away. Strable was told to check in at the nearest alarm box and repeat back the order he had heard; he had received it correctly. Central Station then instructed Officer Strable to report to the east side station and report to Lieutenant Steve Molnar. A set of orders again was given, and Molnar confirmed the communications.

Requesting Radio Funding

Police officials were pleased with the tests and immediately planned to ask City Council members for the funding of a radio system.

History shows that the request in August for radios was rejected. This was partly due to the fact just a few months prior (February 1921) $100,000 in city bonds were issued to cover the cost of Police and Fire equipment. The bonds covered the costs of six new police cars, 13 motorcycles, a new combination fire truck pumping engine, fire alarm switchboard, 70 fire alarm boxes, 50 police alarm boxes and 90 new police signal flashes. No funds were left for a radio system.

Police Radio for Toledo (Finally)

The Detroit Police department ultimately became the first to adopt radio-dispatched policing with a single patrol car. It wasn’t until nine years after those initial Toledo tests in 1921, that the Toledo Police Department would finally use radio-dispatched policing.

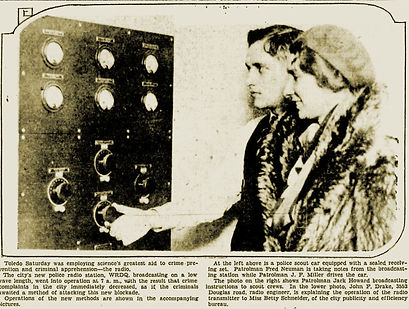

At 7am Saturday November 8th, 1930, Radio Engineer John Drake brought the transmitter of the police radio station “WRDQ” to the air from the alarm building at Beech and Ontario streets. The Toledo department had equipped five speed cars with radio receiving sets that were built into the dash boards of the vehicles.

The first order broadcast by dispatchers from the station was a “BOLO” to be on the lookout for a stolen Willys-Knight Sedan from Sulphur Springs Road. Edward Rigby, assistant radio engineer from AM950 WWJ Detroit, was appointed as an engineer of the Toledo station, bringing Toledo’s radio ties to Detroit full circle.

Further reading and research:

The Development of Police Radio in the United States

WWJ, The World's First Commercial Radio Station

The History of Land-Mobile Radio

Western Electric Advertisement

Steve Pietras is an engineer at WTVG 13abc and a researcher of local radio history. Joeseph Boyle was a history teacher at Waite high School and worked on this story before he recently passed away. His life accomplishments fueled the desire to complete this project. Beth Thieman is a retired Toledo Police Officer and volunteers at the Toledo Police Museum Michelle Hall Wheaton is a volunteer researcher for the Toledo Police Museum